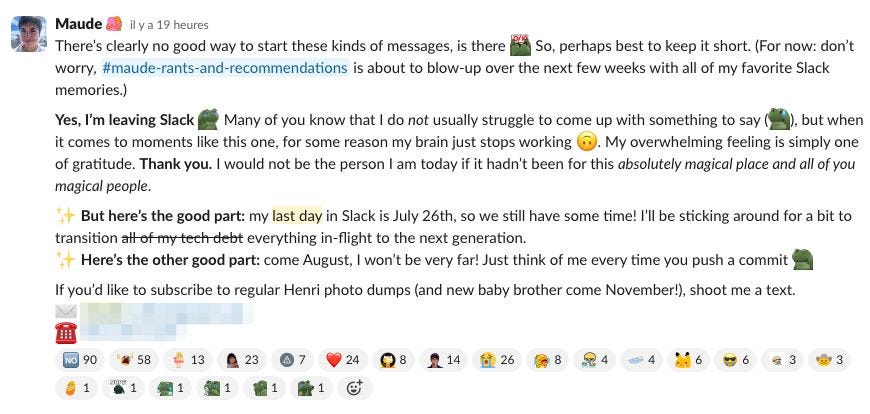

On leaving Slack

The last eight years have been an absolute privilege. In so many ways, I grew up at Slack. I’m forever grateful to the founders; the astounding folks I’ve worked with over the years; the ridiculously outsized opportunities thrown my way. The decision to leave wasn’t an easy one, but ultimately, it was the right one.

Some of you might’ve read my post from late January where I talked about my decision to stay at Slack through many, many inflection points, particularly since the Salesforce acquisition announcement in late 2020. If you haven’t yet, I’ll be referring to it quite a bit here, so it might be worth a peek.

Unsurprisingly, in the six months since, the pace of change at Slack hasn’t slowed, and the inflection points have kept coming.

Yearly planning

In February, it finally happened. We’d reached the end of the years-long roadmap I’d drafted when I originally founded the Backend Performance Infrastructure team in March 2020, the team responsible for all of Slack’s load test and backend performance tooling.

Our load testing tool, Koi Pond, was now fully-featured in a way I’d only dreamed of. Product development teams were independently running multiple tests per week using the platform, ensuring Slack remained scalable and performant for all of our customers well before new features made it out to production. (Seriously! In my last six months, we ran over 100 ad-hoc feature-related load tests without a sweat!)

Simply put, it felt to me like we’d done it.

Certainly there was still quite a ways to go with regards to improving the culture around performance at Slack. I’d long wanted to find a creative way to get product managers to understand (and care about) the performance of the features they owned. We also needed to develop a strategy whereby engineers could take features developed along our “prototyping the path” philosophy and more deliberately render them production-ready; that is, ensure they were sufficiently robust, scalable, instrumented, and well-tested enough to roll out to our entire customer base, and, perhaps most importantly, for these features to function reliably long-term within the broader Slack ecosystem. Performance and scalability are ever-green problems! It’s a huge part of what I love about solving these kinds of problems.

That said, in the seven years since I’d started working on performance at the company, Slack had gone from being completely unusable on a team of 50,000 users (of which maybe only 35,000 were simultaneously active), to comfortably sustaining upwards of 1 million client connections on a single team, no sweat. That’s huge, and, yes, we’d done it.

Departures

The most important inflection point came in early May, when two of my most important mentors left the company on the same day (which, they promised, wasn’t coordinated). They’d kindly given me weeks of notice, so I’d had nearly two months to sit with the news and digest it. But, to be quite honest, it wasn’t until their Slack accounts were disabled that it really began to sink in. I’d leaned on these two veteran engineers for years: soliciting their opinions on everything from company culture to technical roadmapping. They’d been my go-to DM for dissuading me from making rash decisions. They’d always ask the hard questions in my RFCs. They’d gut-checked my spicy takes before I broadcast them in rather large, public Slack channels.

A few weeks before their departure, I asked them who they thought could fill their shoes. I’d been drawing a blank. I’d been looking around at my peers at the Senior Staff level, and those above me at the Principal level. I was terribly unmotivated to invest the time and energy required in rebuilding a similar relationship with anyone else. With some, I simply didn’t see eye-to-eye; others were close friends, too close to serve in the same mentorship capacity; others worked on completely distinct parts of Slack’s architecture, and wouldn’t have been able to guide me from a technical perspective as effectively as my previous mentors had.

That’s when I decided that it was finally time for me to leave Slack.

Compensation Cycle

It’s no wonder all these incredible senior engineers who’d been at the company for ages were moving on. To put it bluntly, Salesforce wasn’t providing hefty-enough RSU refreshers to incentivize long-timers to stick around.

When I joined Slack in late 2016, I received a very generous initial grant as a junior engineer. Slack continued to award me with hefty refreshers regularly, up until the acquisition closed in July 2021.

In 2022, about 66% of my total compensation was equity.

In 2023, equity made up about 53% of my total compensation. In total, I only made about 80% of what I made in 2022.

In 2024, had I stuck around, I would’ve similarly made only about 80% of my 2022 take-home.

In 2025, I was anticipating a further 35% drop in compensation, entirely due to lack of equity refreshers. In total, I’d only be making about 70% as much as in 2022.

In 2026, I’d be facing a staggering 50% decrease in total comp down from 2022.

Even though I’ve been gaining in seniority and tenure, my compensation has been steadily decreasing for the last few years. It’s not a great trend.

Below, you can see the value of my quarterly stock grants starting with October 2022 (with accurate historical value, reflecting the value of CRM at the time of vest), running through April 2028, assuming the stock price continues to hover around $250 per share.

A well-timed series of reach-outs

As though the universe just knew I was ready to try something else, within the next few weeks, two friends reached out. Neha was looking for advice with regards to capacity planning, scaling, and performance at GitHub, and the other was reaching out to see if a year later, I’d reconsider joining his growing engineering organization.

After another round of interviews, including a spur-of-the-moment application to OpenAI (which did not go well) and Anthropic (which went surprisingly smoothly), I was weighing three offers.

It came down to a few key factors, in decreasing order of importance.

What kinds of problems did I want to solve? Many of the same things I’d been working on at Slack for years: scaling, performance, capacity, reliability, and load testing. Most importantly, I wanted to work on big, gnarly technical debt problems that were preventing the company from growing.

Who would be my mentors? Given my Slack mentors’ departures ultimately triggered this landslide, it was imperative that I meet my peers and potential mentors at each of these jobs. I wanted to know how they tackled technical problems, what they found most difficult, their opinions on building and sustaining healthy engineering cultures, how they communicated at every level of the organization, etc. How I felt walking out of these conversations played a huge role in my decision.

How much stability and predictability did I need? I have long been nostalgic for Slack’s early days, but I wasn’t looking to recreate that (somewhat hectic) experience somewhere else (for now). I was primarily looking for those big, gnarly tech debt problems somewhere with a high level of stability. At this point in my job search, I was 19 weeks pregnant with my second. (Now, I’m entering my third trimester!) Wherever I’d land, I’d be looking at roughly two months of onboarding, followed by a four to five month parental leave, and then another potentially difficult re-onboarding as a mom of two.

I’ve always had a very difficult time stepping away from work. It wasn’t easy adjusting to standard hours after having my first, nor was it easy adjusting to leaving him in someone else’s care for a full work day. I still feel the pull from both directions all the time. This next job needed to have a strong, well-established culture of “work hard, go home”, with a manager that’d keep me in check.

I got lucky. With two of these options, I’d be reporting directly to folks I’d known for years. With both, I knew I could be completely transparent. It’d be one absolutely crucial piece of social capital I wouldn’t have to rebuild from scratch.

Did I love the product? To quote my previous post, “knowing that I’m contributing to building the tool that I love and spend most of my day using is a big deal.” After Slack, which tools did I find myself using the most frequently, day after day? Which which product did I have the most affinity? Which mission appealed to me, personally, the most?

Did I want a more senior title? Yes. Sure, there was a chance I’d eventually snag the principal title at Slack. But the more time I spent butting heads with some of the existing principal engineers, the less I wanted the promotion. Two of the three offers were for principal roles.

Did I want more money? To put it bluntly, each of the three offers significantly out-compensated Slack, especially long-term. They were all very compelling. I got very lucky. But, I didn’t end up choosing the job with the biggest potential financial upside.

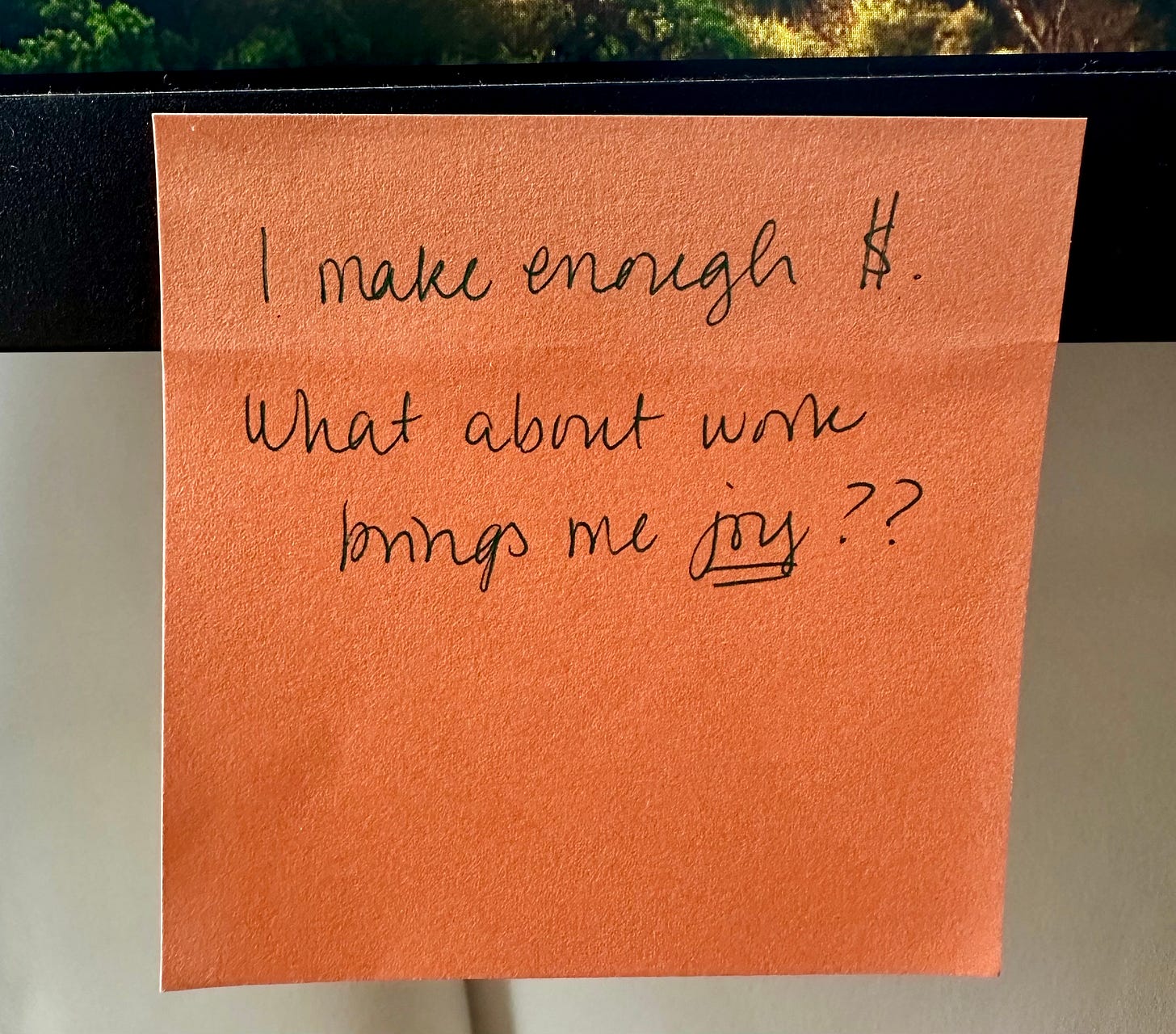

I’ve had a sticky note on my monitor for the past year that’s kept me in check throughout the end of my tenure at Slack, and this entire interview process. It says, “I make enough money. What about work brings me joy?"

Ok, Maude, so where are you going?

With all that, I took a principal gig at GitHub working on the Core Productivity team led by my friend, the fabulous Neha.

They have the kinds of problems that I fall asleep thinking about, the peers who’ll take me to the next level, the stability of a well-established company, a product I love, and the title and compensation to match.

I start next week 😊